Understanding Social Circles

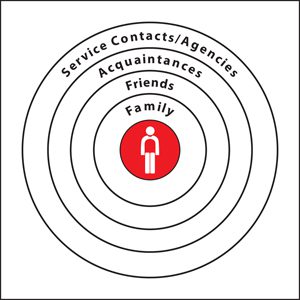

According to Derrick Dufresne, (Five Star Quality Defined, October 2008, Dufresne and Mayer), successful community inclusion can be measured by the amount of people one has in his or her social circles. Social Circles, something we all have in our lives to varying degrees, can be thought of as concentric rings, similar to those of a dart board or bulls-eye, with each of us as our own center. Each ring, radiating outward, represents a different level of support or social connection. The order of these circles, reducing outward the level of connection, or intimacy, might be defined as follows: Consumer-Family-Friends-Acquaintances-Contacts-Agencies-etc.

The social goal for each of us, for each citizen, would be similar to that of scoring on a dart board or bulls-eye: it is most beneficial to get as close to the center as possible. Similarly, the closer a person in our lives can be placed to us in these rings of influence, the more this person benefits us in our lives. With darts, though, as in life, building one’s grouping close to the center is always more difficult to achieve.

A Social Reality Check

Studies show that the average non-disabled person in community can count around 150 people in his or her various social circles, a number that falls in line with British anthropologist, Robin Dunbar’s “Rule of 150″ which speaks to the capacity of the human brain to formulate and maintain relationships.

Unfortunately, studies also show that for individuals living with significant disabilities, the number of people in his or her social circles is around 15. This number, merely 10% of the norm, accentuates the problems created by communities that fail to provide natural and equitable opportunities for people with disabilities to live and interact freely. Additionally, these individuals state that their closest “friends” are often those people in their lives who provide them with daily support, in essence, those “paid” to be there.

For this disparity to change, community and its views toward disability needs to change. In an effort to build more inclusive, understanding communities, the Ability Center is working to build community partnerships with organizations in the Toledo and northwest Ohio area. If you would like to know more or, more importantly, play a part, individually or organizationally, please contact us at the number above or email Dan Wilkins, Director of Special Projects.

The Process of Cultural Shifting

by Al Condeluci

From the book, Cultural Shifting

TRN Press, 2002

“Humans are the only species who is not locked into their environment. Their imagination, reason, emotional subtlety and toughness, make it possible for them to not only accept the environment, but to change it” –Jacob Bronowski

The term “cultural shifting” is used in this article to describe the process of new or unique items becoming part of an existing community. That is, when a new person, product or idea becomes accepted as viable in the community, then a cultural shift has occurred. The process of cultural shifting is described more fully in the book, Cultural Shifting (2001) of which this article is a direct extrapolation.

The Metaphor of a Bridge

The challenge of cultural shifting is best understood when thinking of the concept of a bridge. Bridges are interesting structures as they blend two important notions, the simplicity of connecting two points, and the complexity of the engineering necessary to make the connection. This blending is clear when you look at the challenge of seeing the reconnection of people to community. The challenge is simple as we try to find ways for people, who are disconnected, to be reunited. The complexity is in making this happen.

A vivid example of this is when the change agent looks at the inclusion of people with disabilities back to the mainstream of the community. To understand this example however we must appreciate the powerful forces of exclusion that precede the challenge. That is, historically people with disabilities have been perceived out of a medical model of deficiency and dysfunction. In my books, Interdependence: the Route to Community (1991, 1995) as well as Beyond Difference (1996) the effects of the medical model and the stigma of difference that have created formidable cultural realities leading to community devaluation are explored. In these books I make the point that the medical treatment model has resulted in people with disabilities being seen in the context of inability, problems or incapability.

With this metaphor of a bridge the change agent can think about the individual with a disability on one side of reality, and the community on the other side. The goal for rehabilitation is to assist the person with the disability move from being excluded on the one side to joining the community at large on the other side. In this example, the gap between the person and the community can be represented in the problems or deficiencies the person is seen as having.

When considering this metaphor it seems clear that the problem or the reason that the person with a disability is off set from community is due to their differences, disability or perceived problem. Given this reality the medical model suggests that the best way to get people from one side of the illustration to the other is to focus the problem or in this case, the disability. In most human service programs this is exactly how the issue of inclusion is addressed. That is, conventional wisdom (the medical model) says that we try to attack or mitigate the differences so that the person can be more easily included into the community. Indeed, in my previous writing I explore this medical model approach in much greater detail. This conventional approach is a linear, and microscopic approach to the inclusion of people with disabilities. It suggests that if we can fix the problem, we can more easily get the person included. The major target for change is the person with the difference.

Although this approach has been practiced for years, in essence it has not led to real community inclusion. We have moved people “into” the community but not really helped them become “of” the community. To continue to position the person with the disability as the problem and to try to change them is to chase the wrong butterfly. This is not how culture has shifted.

Rather than to put emphasis on the person and focus attention on to their differences, I am suggesting that we re-think that approach. Indeed, consider the example of a disconnection between two points. That is, much like our illustration above, if you find yourself at point A and you are interested in getting to point B, but there is a river in your way, one might see the river as a problem. To this end, we might seek out help from an engineer as to how we might mitigate or get rid of the river so that we can pass to point B safely.

In some ways this is how the medical model frames the problem of inclusion for people with disabilities. It suggests that the way to get people included in the community is to fix the problems they have. That is, fill in the river!

However, when we use the metaphor of a bridge, the challenge changes from seeing the river as a problem to thinking what other ways we might safely pass over. Obviously, the focus turns to what it might take to build a bridge. In this shift of thinking, the river is not a problem, but a reality to be addressed based on the strength and stability of the shorelines where we plan to anchor the bridge. Consequently, the more important factors are not the problem posed by the river, but the strength that can be garnered to build the bridge.

To this end, to create a real shift in culture follows this metaphor of a bridge and demands that the change agent think about four critical steps. These steps go contrary to the medical model and in many ways how the human service system relates to people with disabilities. To my way of thinking, however, this is the only way we can get people truly included in the community.

Four Steps to Cultural Shifting

When thinking about how any new person, product or idea can be incorporated into the existing culture the following four steps are always present. As we explore these 4 steps keep in mind how they may have worked for you as you have attempted to incorporate any thing new into your community.

Step 1 – Find the Passion or Point of Connection

As with our bridge metaphor, finding the key points of strength and passion is the first step to cultural shifting. To build a strong bridge we must have a solid foundation to assure the bridge will be safe for passage. For the passage of people, products or ideas into culture require the same strength. To this end we must identify all that is strong or good about that which we hope to shift the culture around.

In many cases people know their passions and interests and are quick to tell you if your bent is toward looking for the positives. With other folks you have to dig. In the work we do with our agency, we often-meet folks who have been so sheltered or inexperienced that they do not readily display their passions. Some people have been so devalued that they cannot seem to find their passions at all. In these types of situations we must give the time and space necessary for people to identify those points of connections. This only happens when people feel valued and respected. It also happens when we welcome and include those who have a history with the person help uncover the passions. Families or other relations have been invaluable for the capacity-building work we do in Pittsburgh.

When you really think about it, this process is the same one we try to use with our children. One of our primary efforts as parents is to discover the interests and capacities of our children so as to connect them to communities that celebrate those same interests. Often this is a discovery process. This was driven home to me when just this past spring my wife and I spent a Saturday cleaning out our garage. As we found and removed old bikes, cameras, hockey sticks, baseball bats, a ballerina tutu, an old trumpet, and other items, I realized that we had identified the relics of culture. All of these items were potential interests we were looking for with our children. Ones that resonated for our children created the steps to community for them. Others became artifacts to our anthropological process for community inclusion.

Step 2 – Find the Venue or Play Point

With cultural shifting, once the change agent has identified the positive capacities for inclusion or incorporation, the next critical step is to find the place that the person, idea or product will relate. Quite simply, finding the setting where the person, idea or product might be accepted sets the stage for inclusion and cultural shifting.

By venue or play point I am referring to the viable marketplace for the person, idea or product. With ideas or products the change agent can think in the conventional framework of a marketplace. That is, if you have developed a product that is best suited for accountants, your potential marketplace would be with the fiscal offices of a corporation or with and accounting firm. This, or similar marketplaces offer the best possibility that your product will be understood and, hopefully, purchased.

The concept of venue and play point have a clear importance. If you are looking to find a framework of new friends, you have a much better chance of connection if you take a hobby, passion or capacity and join up with others who share that same passion. A good example is the efforts we make with our children when we attempt to broaden their horizon. Let me use my youngest son, Santino as an example. As I write these words I am sitting at a practice field where he is playing football. Earlier this year he asked me if he could try football. He has been interested in the sport and follows the game. Given this interest, I began to look for a venue where Santino might test his interest in the sport and connect with others. I found such a venue with a local group called the Montour Youth Football League. In the process Santino has developed a number of new relationships with children he has just met.

Regardless of situation the bold fact is that people gather. They gather for all kinds of reasons and interests. For every capacity or passion there is a place that people gather to celebrate these passions. Once we get over our habits of segregation and congregation we can come to see that these places are ones that offer a wonderful start point to culture. In these gathering places we can find the key to cultural shifting and the dispensing of social capital and currency.

Step 3 – Understanding the Elements of Culture

In Chapter 2, I identified the key elements of community. These elements include:

1. Rituals – These are the deeply embedded behaviors of the culture that the members expect others to uphold. These behaviors can be formal actions or symbolic activities that members just pick up. A vivid example here for me was the rituals of my college fraternity. After spending the time pledging, we were introduced to the formal rituals that were expected of each brother. After spending a few weeks in the fraternity I also began to pick up the informal rituals that were specific to those of us who were members at the time. In some ways the formal rituals are ones that live beyond generations because they have been deeply sanctioned. The informal rituals are the ones that are developed by the current cohort and are generational in nature.

2. Patterns – As we stated before, the patterns of a culture refer to the movements and social space occupied by the members. Patterns are captured in how the members relate to each other as they go about the business of the culture. Patterns almost always revolve around the territory occupied by the members. As territorial animals we are very rigid and defensive of that which we feel we have laid stake to in joining the culture.

3. Jargon – This relates to the language, words, expressions and phrasing members of the culture use to describe or discuss that which they hold as important. Often these words might be technical or very specific to the cultural theme. Other times the jargon might manifest in sayings or expressions that are not technical, but are widely understood by other members and become important to the exchange of the culture.

4. Memory – This refers to the collective history of the culture. The memory is honored in formal ways by producing yearbooks, annual reports, and other official documents or celebrations that chronicle the actions of the culture. Other types of informal memory also happen within culture by the weaving and telling of stories or anecdotes. Both of these approaches create a living history of the culture and establish the bond that causes members to want to continue the work of the culture. Memory leads to community wisdom.

Step 4 – Finding or Enlisting the Gatekeeper

The final step in cultural shifting revolves around the gatekeeper. The only way new people, ideas or products can successfully enter an existing community is when they are introduced and endorsed by a viable gatekeeper. As we described in Chapter 2, a gatekeeper is an indigenous member of the community who has either formal or informal influence with the culture. These gatekeepers can be formally elected or selected leaders, or they might be one of the members who everyone can count on to get things done. Further, the gatekeepers can either be positive or negative, assertive or unassertive about the person, idea or product being introduced.

These gatekeepers are powerful because they transition their influence to the person, idea or product they are endorsing or rejecting. This transition of influence is the first step to the inclusion of the new thing into the culture. The mere fact that the gatekeeper likes or dislikes the idea is enough to sway other members to their side. Remember, 60% of the membership of any community is usually neutral (or slightly on the negative side) on issues. The gatekeeper uses their power and influence to persuade others to follow their lead. The assertive gatekeeper will readily offer their opinion, the unassertive gatekeeper must usually be asked.

To effectively shift a culture to accept something new requires that the change agent identify and then enlist a gatekeeper to facilitate the passage. This is simple, yet complex in how it plays out. On the one side we know that gatekeepers are a part of any culture or community. We know that 20% of these gatekeepers are positive people interested in taking risks to promote things they feel good about. We know that when the gatekeeper endorses a person, idea or product that other members observe this and open their thinking to the same. We also know that the more enthusiastic the gatekeeper is to the new item, the more apt others are to do the same. All of this makes sense when we think about culture and community.

Finding and enlisting gatekeepers can be tricky business, but it is an essential ingredient for cultural shifting. Change agents must learn as much as they can about gatekeepers to enhance their effectiveness.

“Community is like a ship, everyone ought to be prepared to take the helm” –Henrik Ibsen

The Need for Inclusive Communities

A Parent’s Words…

“Our son has almost no friends. He has no kids his age or otherwise to “hang out” with on a regular basis, to talk to, or to do things with socially. He is almost 16 and he spends most of his time with us, his parents, his 9-year-old sister, and his extended family. We are a very close family and I know he loves us and likes to hang out with us, but he has shared his feelings with us and we totally understand. We are painfully aware, as our son has told us repeatedly over the years and recently, that he feels totally isolated. He feels like people look at him and just see his disability. They do not take the time to talk to him and get to know him. He wants friends, a girlfriend, to have things to do, to go to college and live on his own, and have a family of his own someday. He has cried to us, even recently, about how lonely he feels socially. He feels he has no life outside of his family. It is heartbreaking to us and to him.” – An excerpt from a parent’s letter.

Everyone needs Community.

Community needs everyone.

The Importance of Community

Just as everyone needs love and friendship and an opportunity to contribute, everyone needs community. We all need to know and believe that we belong to something bigger. Whether it is family, friends at work, church or the gym; the lady at the coffee shop that gives us our coffee and scone each day, it is comforting and healthy to be surrounded by people with whom we are familiar; whom we care about and who care about us.

The Importance of Everyone

Equally, no matter “who” you are, “how” you are or what you’ve been told, you are important. You have something unique to contribute. You have a talent, a skill, an interesting insight or story to share. Just by accessing and giving to the community, you bring a unique and necessary perspective to the social conversation, one based on your individual experiences: how you’ve gotten around and interacted with the world, what you’ve been taught and how you’ve been treated. Without you, your perspective and the contributions that you bring, the community is diminished. The Community, to be all it can be, needs you. It needs everyone.

Being “in” versus being “of” the Community

This all sounds great but there is a problem … and it has to do with whether or not one has the opportunity to truly and fully participate; to contribute. It has to do with the fundamental difference between being “in” the community and being “of” the community. Anyone can be “in” the community. We can go to the store, live in an apartment, attend school or church and be “in” the community, but still not be “of” the community. Being “of” the community is much more complicated. Unfortunately, it requires a status of “member” be “bestowed” upon the person or group by a majority of the community. It requires membership be recognized, validated and supported by law makers, educators, employers, public and social service, housing, and medical providers, by the various religious communities and by the general population.

Anything short of this broad acceptance, this whole new way of thinking, and we remain marginalized, perhaps “in” but not “of” community. We remain without a sense of belonging or “real” connection, no sense of equity. Without equity, without voice, we (and our communities) have less chance of developing wholly and healthily. Opportunities to participate become less possible and those left out can only struggle against continued marginalization.

The Struggle Against Marginalization and the Desire for Belonging

A National Organization on Disability/Harris Survey indicates that people with disabilities feel more isolated from their communities, participate in fewer community activities, and are less satisfied with their community participation than citizens without disabilities. In their writings, Derrick Dufresne and Al Condeluci each reference the impact loneliness has on us as individuals. Loneliness, and the isolation it brings, has been proven, through many studies, to contribute to sickness, even death. In her award-winning short story,

Cipher in the Snow, Jean Mizer wrote of an ostracized teen who collapsed and died in the snow after exiting a bus. It is ultimately determined he died from loneliness, from having no real friends in his life. The quote at the top of this page speaks to the loneliness of one young man in the northwest Ohio area and the concern of his mother. He is not alone in his situation. There are people like him and families like his all over the area and world.

Having access to others, to community, has been an elusive dream for many disabled people, especially for those with significant physical and cognitive differences. For as long as records have been kept, people living with disabilities have been regarded and treated differently. Like many marginalized groups of people, they have been feared, separated, isolated, mistreated, ridiculed, put on display and exploited, denied medical treatment, even killed … just for being different.

Often, disabled citizens are discounted quickly; unfairly dismissed as having nothing to bring to the community table. This happens because there exists a paradigm of low-expectation, based upon old or misguided information and deeply entrenched in our community psyche, that equates “disabled” with “unable”.

Think about when there is a moderate to heavy snow. Ever been to a parking lot after it is plowed? Where do nine out of ten snowplow drivers push the snow? Into the accessible parking spaces. Why they do this is no mystery. There is an assumption that the spots won’t be needed; that disabled people “don’t go out into bad weather”. This is no reflection, good or bad, on the plow drivers. It’s just the way people think, especially those with no “real, hands on” experience with people living with disabilities.

Because of this pervasive societal mindset, people living with disabilities are seen as “less than”; “less deserving” of place, of equity, of having a voice. Nothing could be further from the truth.

A History of Contribution

In reality, throughout history, there have been many contributions made by people living with disabilities toward where we are as a civilization. It is unfortunate that little attention has been paid to this aspect of history because, by its omission, we have perpetuated the myth of non-contribution. For example, when we were taught about people like Lincoln and Churchill, Monet and Matisse, Edison and Einstein, more than likely we spent very little time, if any at all, discussing the impact their disabilities had on shaping their lives and influencing their contributions. Without exploration, we simply accept that there was something about them that set them apart, that led them to do what they did in the way that they did it.

We believe, quite probably, that it was the perspective on life gifted them by their disabilities that set them apart; that led them to write the way they wrote, paint the way they painted, compose the way they composed, lead the way they led.

To better understand the roles people living with disabilities can and have played in community and the importance of creating inclusive opportunities, try to imagine where we would be as a humanity without Homer or Socrates, without Keats, Milton or Shelley, without Mozart or Beethoven, or Newton or Franklin. Imagine no Hawking or St. Paul, Charles, Wonder or Bocelli; no Roosevelt, Keller or Tubman. And these are just a few famous names. There are hundreds more who’s names you would know and millions more unknown people living with disabilities, with gifts and talents to share if only we, as a society, as a true community, chose to open our eyes, minds and doors to what is possible.

Yes, everyone needs community … and community needs everyone.

So, Where We Are Now

There has been change. There is more and better access: more automatic doors, better access routes from parking to building, more attention to mobility and usability in stores, better bathrooms. There are audio loops in offices, theaters and performance centers; tactile menus, signage and artwork. There have been improvements in transportation: kneeling buses, accessible train cars, more aware and better trained support staff at airports.

True Inclusion in education has been spreading out slowly from tiny pockets here and there but, as most parents, educators and advocates would agree, has a long way to go. There are disabled people contributing in academia, politics, community service, the arts, theater, television and movies. There are writers of note, painters, musicians and vocal artists. With all of this, employment is still a problem. In a time when America is feeling the effects of an unemployment rate hovering around 10%, unemployment for disabled adults floats in the high 40 percentile.

With 70 million Baby Boomers reaching 55 and 60, Aging in Place continues to grow as a popular option; new housing is beginning to incorporate universal design and the concept of Visitability is being accepted by enlightened developers and municipalities alike.

The additional benefit of all of this access, all of these improvements to the community landscape, is this: these changes don’t just benefit people with disabilities, they benefit everyone. Everyone uses the curb-cuts, the automatic doors, the ramps. What many refer to as assistive technology, designed and intended for those living with various disabilities, in the end makes life easier for everyone.

Better access to community, as mentioned above, provides more opportunity for interaction, for disabled people to live, work and play within the community as a whole. More interaction leads to better understanding and less fear. People are connecting in natural ways, getting to know each other beyond obvious differences. Many are coming to see that living with disability is not a bad thing, just a different thing, and this change in awareness and attitude gives us the best opportunity to move forward, toward a more inclusive community.

Where We Are Going From Here: The Concept of Five-Star Quality

With all of this said, community participation represents the degree of connection a citizen has to his or her physical and social surroundings. As mentioned above, feeling one is a part “of a community” is not just important. It is vital. It is where life takes place. It is where people feel “at home.” Unfortunately, data show that people with disabilities, more than any other minority group, continue to be isolated and set apart from the greater society (A. Condeluci, Cultural Shifting, 2002). And, in most cases, it is nothing “real” about the person’s disability that causes this greater level of isolation and dissatisfaction. The most common barriers to community acceptance reported to Ability Center staff by individuals with disabilities and their family members are less-than-positive attitudes and low expectations (both based upon old myths and stereotypes, not upon anything real) among human service professionals, community professionals, community recreation providers and employers. There is no blame, no reason for negativity here. People act and react according to what they think they know.

If you have no real connection to disability; no history or experience, either personally or through acquaintance, how can you be expected to understand anything beyond what you have read in books, seen in movies or heard from others?

Helping to change attitudes, to create communities more inclusive in their thinking and design, more accessible and welcoming, is a big part of the mission of The Ability Center.

We believe, given real information and support, real answers to real questions, people will begin to consider disability in a different light, with greater respect and equity, and a higher expectation for what is possible. With this new awareness and the natural partnerships springing from newly formed open lines of communication, many of our community partners are redesigning their programs and places to best meet the needs of all citizens. The Ability Center role in these partnerships is to provide ongoing information and support.

Whether it is training for park volunteers, service providers or Leadership Toledo, or looking at blueprints for 5/3 Field and the Huntington Center, The Ability Center helps its partners consider issues important to citizens living with disabilities. The programs and efforts going forward, along with the responsibilities and staff necessary for those programs and efforts, are owned by the Community Partners. The Ability Center steps back, offering support as needed. We’re not on the marquee.

Our job, as the saying goes, “is to put ourselves out of a job.” When the community as a whole becomes aware of the need and ways to be most welcoming to all of its members, people with disabilities will no longer feel or be relegated to “special” programming held at and through disability-related organizations. It will all, from our perspective, be happening “out there”, in community, by and through the community. It happens outside of what Derrick Dufresne, of Community Resource Alliance calls the “Disability Bubble.” This is what we refer to as “Five Star” programming, happening in “Five Star” Communities.

You may also contact the Center at (419) 885-5733 or (866) 885-5733 (Toll-free) or email Dan Wilkins, Director of Special Projects.

Ideas to Build Community

A community is a network of individuals united in pursuit of a common cause. With that in mind, here are some ideas that may assist you in developing a community.

Perhaps some of these ideas can help you create a community that has diverse membership, common celebration and frequent gathering.

Take some time to review this list and see which ones appeal to you. If you come up with some new ones, please let us know. We’ll definitely add them to the list.

- Turn off your TV

- Leave your house

- Know your neighbors

- Look up when you are walking

- Greet people

- Sit on your stoop

- Plant flowers

- Use your library

- Play together

- Buy from local merchants

- Share what you have

- Help a lost dog

- Take children to the park

- Garden together

- Support neighborhood schools

- Fix it even if you didn’t break it

- Have pot lucks

- Honor elders

- Pick up litter

- Read stories aloud

- Dance in the street

- Talk to the mail carrier

- Listen to the birds

- Put up a swing

- Help carry something heavy

- Barter for your goods

- Start a tradition

- Ask a question

- Hire young people for odd jobs

- Organize a block party

- Bake extra and share

- Ask for help when you need it

- Open your shades

- Sing together

- Share your skills

- Take back the night

- Turn up the music

- Turn down the music

- Listen before you react to anger

- Mediate a conflict

- Seek to understand

- Learn from new and uncomfortable angles

Five Star Quality Defined

Derrick Dufresne

Mike Mayer

Senior Partners

CRA: Community Resource Alliance

October, 2008

www.craconferences.com

To help provide further definition, this is a follow-up to Beyond Accreditation Five Star Quality (doc), the first article we wrote on the Five-Star Quality Philosophy. In the Five-Star Quality model there are several key elements that must be clearly understood in order to accurately describe the degree of quality that exists.

At the same time, it is not our intent to come up with a chart that details percentages, logarithms, or can be scientifically proven. There are many ways to accomplish the different levels of quality. It is not possible or necessary to describe every way that these things can be done. It is far more important that we have a clear understanding of what the outcomes are for each level.

We hope to provide information that will help the reader to better understand and be able to identify the levels of quality by the outcomes evident. Thus, this is a system that is not about “paper compliance” or abstract policies and procedures, but rather something that we will be able to define by what we see when we see it.

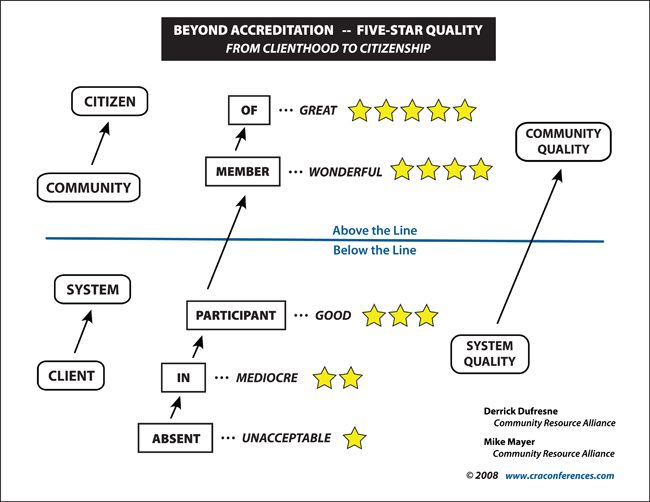

As can be seen by looking at the accompanying chart, the first and greatest distinction is about what is above or below the line. This is the key line of demarcation that needs to be described and evaluated. As is clear: One, Two, and Three-Star Quality fall below the line. Four and Five-Star Quality sit above the line. The distinction between below and above the line is most important.

We also find it is often the least understood distinction. In particular, we find that human service agencies continue to ask (or even assert) that people can have Four or Five-Star experiences within their programs. The Five-Star Quality model does not support that framework of thought. This is not a model of quality where the agency tallies up enough “experiences” to qualify as having reached a certain level.

In addition, we find that many agencies often mistake what is actually, at most, a Three-Star experience with what they perceive to be Four or Five-Star experience. It is this misperception that we would like to address and, hopefully, clear up now:

As long as a person’s experience is contained within the “Disability Bubble” (meaning as part of a program that is operated by an agency for people who have disabilities) it can never be better than Three-Star Quality.

Another key element of the evaluation process is the determination as to whose name is found on the “marquee” of the operation, even if it is held in a generic community setting. If the program, business, letterhead or marquee (sign) has the name of the human service/disability agency at the top, it can never be more than Three-Star Quality.

Having said this, we want to emphasize that Three-Star Quality is very good – it is the best of what traditional service systems have available. In comparison to much of what we see currently in operation – even after 58 years of community services (within the Disability Bubble), Three-Star Quality could be considered great quality (but only within the Disability Bubble).

Most typical accreditation services would consider this level of service to be worthy of their highest evaluation. Three-Star Quality means that an agency has at least crossed the point of no longer seeing that all supports for people with disabilities need to be self-contained – meaning that they understand that not all services and supports must be provided within the walls of the agency, by agency employees or volunteers. Most importantly, it means that the agency helps people enrolled in their services not to just “be in the community” but to become truly participating members of their community.

This, frankly, contrasts with Two-Star Quality situations we see still incredibly prevalent in human service today. Any type of sheltered employment, group home, or other operation that can be distinguished as self-contained, is clearly Two-Star Quality. These operations may meet all of the licensure requirements, have great health and safety records, hold multiple accreditations and have community outings on a regular basis, but they are still only Two-Star programs in the Five-Star Quality Model.

Some human service agencies, despite what they believe are their many efforts and innovations, are increasingly upset and disappointed that we consider them below the line. They desperately seek (and rightly so) to have their efforts acknowledged; for someone to recognize the risks that they have taken (often with little to no funding support). They believe they must be doing Four or Five-Star Quality work because, a) it is so much different than that which they used to do and, b) the lives of the people they work with have improved (at least from their perspective).

Further, we have had people point out to us their organization’s awards, accreditations, positive publicity and/or accolades received. We’ve even been in some situations where the agency has pointed out partnerships with communities and with generic community services that believe that this must certainly be evidence of Four or Five-Star Quality.

Unfortunately, we beg to differ. While efforts like these above are valuable and should be a part of the lives of people who have disabilities, the truth regarding the march toward Five-Star Quality is that a service or support can only be above the line if it is not only community–based but community led. This means that a generic, non-disability specific community organization, business, or group of citizens must be at the forefront of the community effort while the human service agency, if it needs provide any support at all, provides that support behind the scenes.

The biggest hurdle, unfortunately, which disability-focused human service agencies can never overcome on their own, is that the name on the marquee, the ownership of, or the leadership for the program, service or activity offered, must come from a non-disability focused organization. The name on the marquee must be a community-identified and a community-owned venture.

The implications for disability-specific human service organizations are obviously huge. It means that their name goes from the top of the letterhead (or marquee) to the bottom. It means now that the tag-line is likely to read “with the generous support of XYZ Human Services”. The disability agency has to become an invisible support to the community effort rather than its primary mover.

Thus, the agency becomes a support for building community competency – so that the community can help people who have disabilities become functioning citizens –with the least amount of specialized support from the human services agency as possible.

This mindset represents a paradigm shift. Success can no longer be measured by the number of employees, the size of the budget, the number of programs that it operates, awards, accreditation, or how well it is known in the community. If an agency is to embrace this clear redefinition of success, it will obviously require a significant transformation by the organization as a whole.

The organization moves to the background, and the community, along with the people who receive support, move to the foreground. Rather than continue to be identified as a “client” of a disability-focused agency, the new identification for this person receiving support will be as an employee, a member of the (non-disability specific) community organization, a team member of the event, or a full citizen participant of the community opportunity.

Far less important, is whether or not the agency is Four or Five-Star Quality. These concepts will coalesce as the agencies and their communities continue to develop. This can be debated, discussed, and resolved as we move forward.

For now and for the immediate future, Four-Star Quality is defined as when an organization begins a project, such as a supported employment project within a factory, but then turns it over to the management of the factory, providing support to the various departments of the factory so they are able to meet the needs of the individual employees with disabilities.

Another example could be the dance that was always sponsored by the disability-related organization and that others in the community were invited to attend. To reach Four-Star status, the agency turns over the dance planning and execution to the local Elks Club and the agency’s name now is only identified as “with support from”, as is the local radio station that promoted it, the grocery store that provided food and decorations at cost, etc. The agency’s role becomes that of invisible support as trainers, consultants, greeters, clean-up staff, etc. They do not present themselves as “obvious staff”.

An example of how one agency demonstrated Five-Star Quality may help here:

The adult services division of Sor County Board of MR/DD was spun off to become a free standing non‐profit organization – First Consideration, Inc. (FCI). Initially, FCI only served people who had developmental disabilities but they were doing so in a public venue that was not identified as specific to people who had disabilities – as the County Board-owned and operated workshop had been. (One-Star becoming Two-Star)

FCI began providing supported employment services for a small group of individuals who had disabilities at local businesses. (Three-Star)

FCI worked with one of the employers, Daem, Inc., to take over the job-coaching duties for people employed at the employer’s place of business with the promise of being immediately available if needed. FCI worked with HR, employee assistance programs, and the co-workers of the individuals who had disabilities at Daem until they felt confident managing the situation. (Four-Star)

FCI eventually spun-off their supported employment services into another nonprofit – Work Placement Services (WPS), which operated out of a storefront business in the downtown area. WPS was actively involved in helping people who needed work – people who did and did not have obvious disabilities. WPS did not advertise themselves as being for people who had disabilities but rather as a community resource.

When Daem downsized their local operations, WPS got the contract to assist those employees who had been laid-off from Daem. Some of the people who did not have obvious disabilities were trained how to be job coaches to assist people who did have disabilities to get and maintain successful community employment – meeting a need of both local businesses (who needed good employees) and FCI who needed to have individuals with disabilities be successful in community employment.

Further, Daem was pleased that at least some of their former employees had found employment locally while, concurrently, Daem’s outplacement and unemployment costs had been effectively managed. (Five-Star)

To use the dance example to cover all of the categories:

One‐Star: A dance for people with disabilities that is sponsored by the human services/disability organization held at the sheltered workshop. (The person is absent from the community).

Two‐Star: A dance for people with disabilities held at the local YMCA that is sponsored by the human services/disability organization. People with disabilities are “the audience” even though some people who do not have disabilities may attend. (The person is “in” the community)

Three‐Star: A dance for the general community is held at the local YMCA sponsored by the human services/disability organization in partnership with the YMCA and other organizations. People with disabilities from that agency and possibly others are in attendance. (The person is a participant with the community).

Four‐Star: A dance for the community held at the local YMCA and sponsored by the YMCA and other community groups and the human services/disability organization provides “invisible” (not publicly recognized) supports to the YMCA and the rest of the community to enable people with disabilities to fully participate as anyone else would. People with disabilities from throughout the community are clearly welcomed and may or may not have paid supporters assisting them. (The person is a member of their community).

Five‐Star: A dance for the community held at the local YMCA and sponsored by the YMCA and other community groups. People with disabilities from throughout the community are clearly welcomed and may or may not have paid supporters assisting them.

The human services/disability organization is not obviously a part of the dance planning, coordination, etc., but rather acts as consultants and trainers to the sponsoring organizations to help them have the capacity to support people with disabilities fully to participate as anyone else would. The human services/disability agency personnel are “invisible” but remain “on‐call” for the sponsoring organizations. (The person is “of” their community – meaning the community has the ability to meet any immediate needs of the individuals who have disabilities).

In closing, what must become increasingly clear is the difference between One, Two and Three Star Quality and everything above the line. This is the line of demarcation that, for some, will either be raising the bar to new heights, as an exciting prospect, or a bridge too far, whose cost, with all the implications that might follow, is just too great to the organizational identity.

If indeed it is a bridge too far, our only hope is that we can be honest enough to discuss the reasons and the rationales for the decision looming, with the hope that we can find solutions. We hope that the discussion does not turn to “the community is not ready” or “we’d never be able to raise any more money” or “that’s just not realistic”.

We know, for some, it will be a bridge too far. For others, it will be a chance to move from clienthood to citizenship. We believe that all people, including people with disabilities, deserve Five Star Quality and, through full participation in truly inclusive programming, to be “of” their community.

Community and Social Capital

by Al Condeluci, PhD

Community is a network of people who regularly come together for some common cause or celebration. A community is not necessarily geographic, although geography can define certain communities. To come to an understanding of community is to appreciate that community really is based on the relationships that form, not on the space. In fact, space can be an abstract notion when it comes to understanding community. Think about the global community created by the Internet. These communities are not bound by geography, but are relationships forged in cyberspace.

The term “community” is the blending of the prefix “com,” which means “with,” and the root word, “unity,” which means togetherness and connectedness. The notion of being “with unity” is a good way to think about the concept of community. When people come together for the sake of a unified position or theme, you have community.

The term “culture” is analogous to community, but culture relates more to the behaviors manifested by the community. People bound together around a common cause create a community, but the minute they begin to establish behaviors around their common cause they develop a culture. In this way, culture is the learned and shared way that communities do particular things.

This basic approach to community and culture blend three key features. One is the fact that community is a network of people. Often these people may have great differences or even distances between them. They can be different in age, background, ethnicity, religion or many other ways, but in spite of their differences, their commonality or common cause pulls them together. The similarity of the common cause or celebration is the second key feature of community and the glue that creates the network. Regardless of who the members of the network are as people, their common cause overrides whatever differences they may have and creates a powerful connection. Finally, as the collection of people continues to meet and celebrate on a regular basis, they begin to frame behaviors and patterns and become a culture, the third key ingredient. These regular meetings bond the community members as they discover other ways that they are similar.

Again, these three key features are:

- Diversity of membership

- Commonality of celebration

- Regularity of gathering

One of the most important facets of community is that it promotes a sense of social capital for the members who belong. Social capital refers to the connections and relationships that develop around community and the value these relationships hold for the members. Like physical capital (the tools used by communities, or human capital – the people power brought to a situation), “social capital” is the value brought on by the relationships.

L.J. Hanifan first introduced the idea of social capital in 1916. He defined it as: “those tangible substances that count for most in the daily lives of people: namely good will, fellowship, sympathy, and social intercourse among the individuals and families who make up a social unit …The individual is helpless socially, if left to himself … If he comes into contact with his neighbor, and they with other neighbors, there will be an accumulation of social capital, which may immediately satisfy his social needs and which may bear a social potentiality sufficient to the substantial improvement of living conditions in the whole community. The community as a whole will benefit by the cooperation of all its parts, while the individual will find in his associations the advantages of the help, the sympathy, and the fellowship of his neighbors.”

More recently, Robert Putnam (2000) defined the concept of social capital as: “referring to connections among individuals-social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them … [It] is closely related to … civic … virtue … A society of many virtuous but isolated individuals is not necessarily rich in social capital.” (p.19).

Other sociologists suggest that social capital is enhanced by social currency. This idea is how social fodder links people together. For example, a popular person who is the life of the party might be regularly included in activities. To this extent he is strong in social capital. His jokes and storytelling, the items that make him popular in the gathering, are the social currency he exchanges.

Think about the many communities with which you are involved. People who might be different from you in many ways surround you – your family, your work team, your church, or your clubs or associations – but the commonality of the community tends to override the differences you have and create a strong norm for connections. The exchange is based in social currency. Further, these relationships become helpful to you for social reasons. Sociologists call this helpfulness “social reciprocity.”

Social capital is critical to a community because it:

- allows citizens to resolve collective problems more easily

- greases the wheels that allow communities to advance smoothly

- widens our awareness of the many ways we are linked

- lessens pugnaciousness, or the tendency to fight or be aggressive

- increases tolerance

- enhances psychological processes, and as a result, biological processes

- This last point prompts Putnam (2000) to assert:

“If you belong to no groups, but decide to join one, you cut your risk of dying over the next year in half!”

The fact that social capital keeps us safe, sane and secure cannot be understated. Most of us tend to think that institutions or organizations are key to safety. Places like hospitals or systems like law enforcement are thought to keep us safe, but the bold truth is that these systems have never really succeeded in keeping us safe or healthy. Rather, it is the opportunity for relationships that community offers us as well as the building of social capital. Simply stated, your circles of support and the reciprocity they create are the most important element in your safety. In fact, it has been suggested that social isolation, or the opposite of social capital, it responsible for as many deaths per year as is attributed to smoking.

When we consider social capital for people with disabilities, we must recognize the void. We know that people with disabilities still are separated from the greater community and mostly involved in special programs or services designed for them. In these realities, the major outlet for social capital is found only within the borders of the special programs. To this extent then, the relationships that constitute the social capital of many people with disabilities are other people with disabilities. The narrowness of this reality leaves a significant void.

Consider the notion of reciprocity. The more you become connected with your community, the more people begin to watch out for each other. If one day a regular member of your group doesn’t show up, a natural inclination would be to check up on them. This sense of group reciprocity is what leads to individual safety.

If the major social capital outlet for people with disabilities is other people with disabilities, then the reciprocity factor can become narrow. The more narrow the confines of reciprocity the less impact it offers.

Putnam’s ideas of how social capital builds tolerance and lessens pugnaciousness also fit closely to the concept of cultural shifting. Anthropologists have found that for communities to get better, new and different ideas, people or products are necessary. Yet intolerant and angry communities are not as open or as ready to absorb new things. Consequently, cultural shifting is more difficult when communities remain narrow. Social capital helps build tolerance because the exposure to others challenges us to consider new things. This developing openness then has an effect on pugnaciousness. Simply put, if you become more exposed to difference, anger levels have a greater potential to go down.

This notion of social capital and the blending of similarity of interest with natural diversity of the members create unique phenomena for growth and development in both people and organizations. The drive to find, create or be more than we had before is magically transformed when it is blended with community. The reciprocity developed through social capital is helpful as well for either specific or general reasons.

Many current business leaders understand the notion of community and social capital. Most successful companies and organizations work to create a community sense among their employees. A company can be energized by the idea that people can bond around a mission statement and objective to find mutual success. The relationships that form a bond create opportunities for social reciprocity and build social capital. In fact, about any organization or work force, including families, can lead to a greater sense of bonding, focus and success. Quite simply, community is a universal concept that creates advancement not only in products and ideas, but for people as well.

Cultures and communities have many features, but one key ingredient is regularity. That is, for a community to be viable it must have some regular points of contact and connection. For a family community, this might be annual reunions or the celebration of holidays together. For a religious community, this would be weekly services and holy days for celebration. For organizations this would be regular staff meetings or stakeholder gatherings. For clubs, groups or associations, regular meetings or gatherings formalize the group as a community.

The more people come together the more they find other ways that they are linked. That is, when a person first comes to a community they are drawn by the common interest of the community. As they attend again and again they will find other similarities with people in the community and create a deeper sense of bonding.

Other features of community include the notions of consent, creativity and cooperation. Years ago Robert Nisbit (1972) suggested that community thrives on self-help and equal consent. He felt that people do not come together merely to be together, but to do something together that cannot be done in isolation. Others (Sussman, 1959) identified community for its sense of interdependence. McKnight (1988) described community as a collective association driven toward a common goal.

Indeed, if we think about communities that we know, they all work toward some identified goal. From teaching people new skills, to saving souls, to addressing a common problem, to launching a government, all of these ventures capture the power of community, and then, through their behavior, create a culture. The most vibrant and successful of these communities are the ones that have built more social capital.

Web Sources:

Contact Al Condeluci via email or phone at (412) 683-7100 x 329.

This article is excerpted from Cultural Shifting: Community Leadership and Change (TRN Press, 2002).